tl;dr: Experienced cleantech CEOs leverage China instead of fearing it – enlisting self-interested partners to defend IP and manage risk.

This post was co-written with George Miller, an MIT MBA student who conducted this research while interning with me. A version of it also appeared at GigaOM.

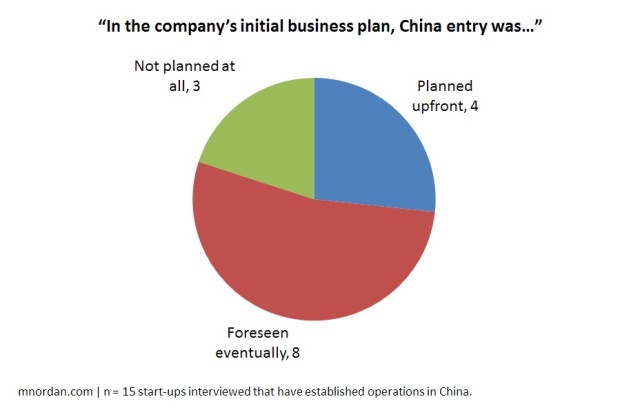

One morning it dawned on me that of the nine energy companies in our Venrock portfolio, a third are focused on China – yet none of them planned it upfront. I figured it would be good to understand how other cleantech start-ups have approached the middle kingdom, so I enlisted MIT MBA student (and fluent Mandarin speaker) George Miller to interview a representative sample and collect best practices.

George spoke confidentially with 15 venture-backed cleantech start-ups that have set up Chinese operations. Every interviewee was either a C-level executive or VP of business/corporate development; the majority were CEOs. Nine of the 15 interviewees entered China primarily to sell into the domestic market, while the balance aimed to export from Chinese manufacturing facilities. The average company is 11 years old and entered China five years ago.

Most of our research findings are confidential to Venrock and the companies interviewed, but some high-level conclusions deserve a broader airing.

China strategies have been mostly improvised. At all of the companies we spoke with, China is a big, board-level deal, ranking somewhere between “an important growth market” and “our sole focus.” Yet only four firms had a specific China plan at the formation stage, and three initially didn’t plan to enter China at all.

Nearly all companies partner. The most common engagement model we found was a joint venture (JV) with a Chinese enterprise, represented by eight of the 15 interviewees. Six have set up distribution agreements but not full-blown JVs. Only one has gone it alone in China, with a standalone, wholly foreign-owned entity that manufactures and sells directly.

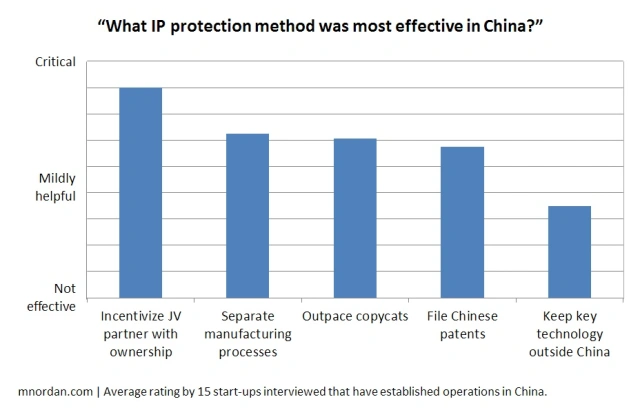

IP is the big challenge. When we asked about key challenges experienced in China, intellectual property (IP) protection topped the list. This is no surprise – tales of IP leakage in the country are legion, with cleantech’s most glaring example being the outright theft of American Superconductor’s wind turbine software. General transparency in business dealings came second, and a cluster of people-related challenges followed. In contrast, interviewees didn’t find market access difficult: We heard that with strong government support and large pools of capital, the risk appetite for capital-intensive projects is greater than in most developing countries.

JVs are the solution. Conventional wisdom says to protect IP by building moats – like splitting manufacturing steps across sites so no one person knows them all, or supplying a key “black box” component from outside China. Our interviewees employ these moat-building tactics, but they think bridge-building works best: The technique rated most effective was forming a joint venture with a large Chinese partner, incentivizing that partner with outsized ownership, and relying on its self-interest to defend the IP. Notably, every interviewee with a JV ranked this tactic the highest.

JVs address secondary problems, too. When we delved into interviewees’ secondary challenges about transparency and people, it turned out that a strong JV partner was effective in resolving them as well. The stories we heard addressed…

…conflicts of interest: “We had no idea that the largest shareholders in [a potential distributor] are also in the seats of power at [the end customer]. Only once you reach the goal line do they open the kimono.”

…internal corruption: “One of the executives we hired was marking up purchase orders and taking kickbacks. He didn’t have a bad heart, and that practice is common in China – so instead of ‘firing’ him, we ‘retired’ him.”

…training: “Because our technology is so unique, we didn’t have trouble attracting and retaining talent. The challenge was educating them on exactly what we do.”

…workforce management: “It’s not just the government that’s socialist; it’s also the labor force. Financial incentives don’t work well. We used vacation time as a key motivator.”

It’s self-evident that these challenges can be mitigated by a strong in-country partner that knows the value chain and manages lots of people.

. . . . .

Chinese joint ventures are no walk in the park. The average JV in our sample was three and a half years old, had taken longer to get going than expected, and was considered too early to call as a success or failure. Interviewees complained about long government approval processes and culture clashes along the way, and we didn’t hear any silver-bullet tactics for doing it right: The best practices were all things you’d expect, including intensive background checks of partner executives, JV agreements that maintain “face” for both start-up and partner (usually relying on profit-sharing), and experienced domestic legal representation. And clearly, you’ve got to be obsessive about picking a trustworthy partner – American Superconductor’s widely-publicized IP dispute is, in fact, with its former JV partner Sinovel.

Despite all those caveats, I drew a clear conclusion from this work. Most cleantech innovation is happening in the U.S., but most adoption will be in growth economies building new infrastructure – with China at the top of the list. Chinese incumbents like Wanxiang, Shenhua, and ENN are scouring the west for technologies to pick up. In this environment, a cleantech start-up can either play defense at the barrel of a financial gun (see A123 Systems), or play offense, entering China on its own terms and timeline. If you’re going to do the latter, be prepared to partner up.

For anyone entering China, the best way to get street smart, with a quick read, is the book “Where East Easts West” by Sam Goodman http://amzn.to/12Lsm0k. Full of nuggets in digestible 3 page chapters. (Not to be confused with a similar title – which followed 🙂 – by Andrew Lam )

Nice post, Matthew. Thanks.

Matthew, nice post. As usual, this feels accurate and timely.