(A version of this post also appeared at Fortune.com. Thanks Dan!)

tl;dr: It’s the team.

I entered the venture capital business two years ago, focusing on seed/Series A cleantech start-ups. It’s kind of like picking a future NBA draft by watching eighth graders play basketball: There are many years’ worth of development to go, and the subjects will look a lot different once they’re all grown up. The key is excellent pattern recognition – identifying the antecedents of success long before it happens.

Pattern recognition is vital for entrepreneurs, not just VCs – if you aim to succeed, it helps to know what other successes have looked like!

Most of my fellow cleantech VCs came to this field from some other domain – often semiconductors or telecom – and brought their pattern recognition biases along with them. The question I found myself asking was “what if everyone’s biases are wrong?” What if we’re picking the wrong eighth graders?

Coming from a career in the tech analyst business, I wanted to find a fact-based way to answer the question, so I assembled a well-defined set of successful VC-backed start-ups and looked for what they had in common. I picked companies that:

- Had achieved unambiguous success, which I defined as an IPO on a major exchange. That’s far from a perfect criterion, I know, but at least it’s clear-cut.

- Went public after 2000, to rule out the boomlet of ’98-’99 energy IPOs (when the Internet bubble’s rising tide lifted all boats).

- Were backed by institutional venture capital. Note that the majority of public cleantech companies have, in fact, not been venture-funded.

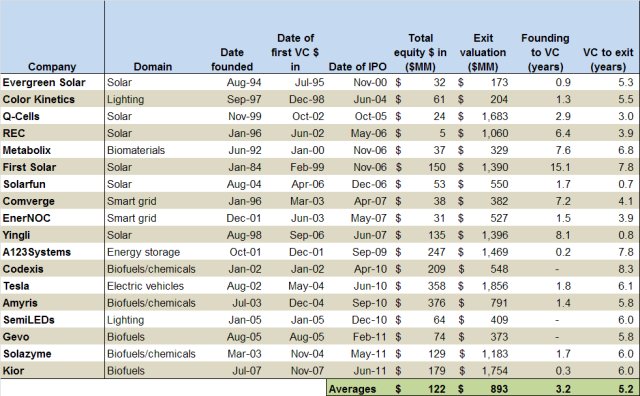

As of today, this sample consists of 18 companies:

(Doubtless there are errors in this data, so please point them out in the comments and I’ll make corrections in a batch. To pre-empt one item, however, note that I included predecessor companies in each firms’ history, which explains First Solar’s founding date.)

(Doubtless there are errors in this data, so please point them out in the comments and I’ll make corrections in a batch. To pre-empt one item, however, note that I included predecessor companies in each firms’ history, which explains First Solar’s founding date.)

What can we learn from this? The average NBA draft pick of cleantech:

- Raised $122 million in equity financing, which excludes grants and debt. The distribution is pretty broad, but I’d note that if you remove Q-Cells and REC as special cases, the floor is ~ $30MM. If a new business plan poses a lower lifetime cash requirement, there should be an airtight argument to justify that claim.

- Went public at a ~ $900 million valuation, also with a broad distribution. If you assumed that investors owned, say, 80% of these companies at the IPO, the lot would have delivered a 5.9x return on capital invested.

- Took 8.3 years from founding to IPO. If you’re signing up to build a cleantech winner, reserve a decade of your life. Note, however, that this elapsed time has shortened for companies that have gone public since 2010, where it averages 6.7 years. Start-ups in this later group received venture financing either right at their founding or soon after it, in contrast to earlier companies which often bootstrapped themselves for years before taking venture capital.

- Survived a 1-in-50 success rate. These 18 companies received their first venture investment between 1995 and 2007. A quick Venturesource search indicates 986 seed/Series A rounds done in cleantech during that period. While there are doubtless further successes to come, particularly from start-ups funded in the later years, the yield so far is 18 / 986 or 1.8% of start-ups funded.

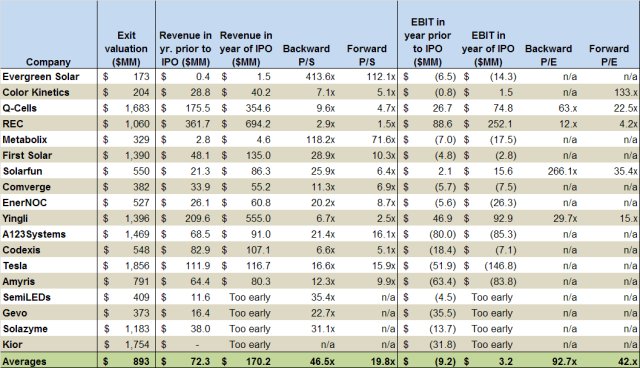

If we include some financial metrics, we learn a bit more. The average cleantech winner also:

- Went public on $72 million in revenue the prior year. With a couple of outliers (SemiLEDs and Gevo), the revenue floor for an IPO has been around $30 million since 2007. This has led to price-to-revenue valuations at IPO in the double digits, transcending their category comparables (for example, A123Systems is still at 4x P/S today despite two tough years, while incumbent battery-makers Exide and Enersys sit well under 1x). Winning cleantech start-ups get valued like high-growth tech companies, not like their incumbent peers, so the latter haven’t informed IPO valuations.

- Was unprofitable at IPO. Only four out of 18 companies – Q-Cells, REC, Solarfun, and Yingli, all in solar – showed an operating profit in the fiscal year before they filed. That situation remained unchanged in the year of the IPO itself, where most companies’ losses widened rather than narrowed.

This analysis tells us what the NBA draft looked like, but it doesn’t say anything about the eighth graders. To learn about them, we need to do some primary research. Here’s how I went about it.

I talked to as many people as I could who were familiar with these 18 companies at their earliest stages. I asked them a simple question: “At the time of the seed/Series A fundraise, how would you have rated [company X] on its technology, its market, and its team – great, middling, or unfavorable?” For each start-up, I strove to speak with at least one investor who did the seed/Series A deal as well as at least one who saw it and passed; however, for many companies I couldn’t pull this off – so let me emphasize that there’s a heaping helping of subjectivity here. With that caveat in place, here were my results:

- Technology doesn’t correlate with success. At the timing of early-stage financing, only about a third of these companies were real technology leaders with strong, differentiated IP (think Evergreen Solar in 1994). If you made picks based on technology alone, you’d have ruled out most of these companies.

- Market attractiveness was anticorrelated. Eight of these 18 firms faced unattractively small markets early on: Demand response was hardly a hot category when EnerNOC and Comverge formed in 2003, electric vehicles evoked little more than the EV-1’s failure at Tesla’s 2002 founding, and Reagan took the solar panels off the White House two years after First Solar’s predecessor Glasstech started up. Another six firms faced middling markets that were large in absolute terms but exhibited some deal-killing attribute, like low/volatile category margins (chemicals, fuels) or ruthless Chinese competition (batteries, LEDs). In most cases, the bit-flip from an unattractive market to an attractive one was driven by regulation (feed-in tariffs for solar, forward capacity markets etc. for demand response, and subsidies like the Renewable Fuels Standard for biofuels).

- Team matters most. The best predictor of success for this group was a killer team, present from the outset in a majority of these companies. (From my interviews, only one of the 18 was a “we’ll fund if the CEO gets replaced” situation.) The most important observation for me is that, most of the time, the founding CEO was the same one who rang the stock exchange bell years later: Eleven out of 18 never changed CEOs, two started life without any CEO and added one along the way (in both cases the founders stayed on), and only five changed leadership midstream. I frequently hear some of my energy VC peers say that there’s so little executive talent in this sector, replacement CEOs must be recruited as a matter of course; the facts don’t support that view.

So – faced with the daunting task of predicting cleantech’s NBA draft eight years’ hence – what am I looking for?

I’m looking for a great team – people who can defy intimidating odds and who show, rather than tell, how they will shape the world to match their will. I accept that additions will be made over time, but I have to believe that the people in front of me can drive a very large outcome in the roles they’re in now. I don’t care whether the market they’re selling into is big today, but I need to be compelled by their vision of what will change to make it attractive during the period of investment. (That forcing function is probably may often be regulatory.) Finally, no matter how impressive the technology is, I won’t compromise on the people (although I’m likely to accept a tradeoff in the opposite direction).

That’s just my take, and I’m fully aware that the error bars around this analysis are huge. But if you agree with any of it, it follows that the best thing cleantech investors can do is attract the brightest minds to this domain. This should be the greatest creative and collaborative focus of our fledgling community.

I might be wrong as this is from memory, but a few comments regarding VC participation…

1. Solarfun – Good Energies came in very close to IPO and substantial (if not majority) of investment was done post IPO.

2. First Solar – Investment made from Walton Estate, not a traditional VC, but more family office.

3. Yingli – who did that? likely similar to Solarfun.

When I shared this with my colleagues there was some debate about whether Solarfun and Yingli should be in the list; the argument is that they were more like opportunistic growth equity/PE deals than anything else. Definitely a judgment call. IMHO Madrone is a really smart VC shop that happens to be a family office, but I believe its predecessor Glasstech Solar had VC investors among the 57 that placed capital in to the co. Thanks Nick!

Matt,

I think your blogpost is a good way to start a conversation, but I am afraid of two key problems I see in your study.

1) Controlling for dependent variable: this is such a common problem in research that people have started to ignore it (the financial world and even HBR are notorious for this). If you only look at successes (only companies that IPO) you are destined to reach biased conclusions. Some companies that did not make your list may have shared the same characteristics (great team, small market, good technology) and still not make it. There may be some other variables impacting the outcome but due to the way you structured your research you are unable to see it. I also see that you are falling into the trap of mistakenly assuming that correlation means causation -they are obviously not the same

2) I was a bit disappointment with your conclusions. Market, Technology, and People are the typical framework that VCs use to analyze investments. I was expecting to see a new parameter. I would say that smaller markets at the beginning is typical of disruptive innovation (Zynga, Amazon, etc..)

I like your call for bright people. Unfortunately, as long as tech continues grabbing much of the headlines and returns, we would see bright people flocking to that sector

Yep — if you wanted to do this right, you’d compare matched pairs of companies longitudinally so that you’d eliminate as many extraneous sources of variance as possible. My aim here was to look for correlations based on a manageable number of case studies with ample public financial data, which confines the scope to (eventually-)public companies. A bright MBA- or PhD-in-training with a lot more time, and the ability to sign copious NDAs, would provide less fuzzy answers — interesting thesis idea?

Yes, I am an MBA from Stanford. This sounds like an interesting project. Let’s chat

Knowing your interest in sports, you should check out Moneyball. It’s about how the Oakland A’s used unique statistical analysis to “pick the best 8th graders”. It was very novel at the time.

Pingback: The state of cleantech venture capital, part 2: The investors — Cleantech News and Analysis