tl;dr: PRIME launches today, bringing a new source of funding – philanthropic capital – to clean energy tech.

How will we scale the world for 10 billion 11 billion people? How will we double the size of the consuming class – people who eat meat and drive cars – without wrecking the climate or fighting resource wars?

How will we scale the world for 10 billion 11 billion people? How will we double the size of the consuming class – people who eat meat and drive cars – without wrecking the climate or fighting resource wars?

A big part of the answer lies in deploying the best clean energy technologies we have today at massive scale. If we’re smart, we’ll focus those deployments on high-growth economies, where we can inflect the arc of consumption and deliver the biggest impact. My firm MNL Partners does this.

But an equally important part of the answer is coming up with new clean energy technologies that are radically better than what we have now. Olympic judges would assign a much higher “degree of difficulty” score to this, because birthing a breakthrough energy technology requires lots of money, time, and risk tolerance – more than the conventional start-up financing system supports.

PRIME Coalition introduces a new funding model for energy innovation that harnesses philanthropic capital. PRIME aims to birth true breakthroughs: clean energy technologies with planetary-scale impact.

. . . . .

Why do we need better clean energy technologies in the first place? Because the ones we have today aren’t that good. Don’t get me wrong – photovoltaics, wind turbines, and the like are the best technologies we have now and we should put them everywhere we can. But on a number of key metrics, we’ll have to do better to support a growing, prosperous world. Consider power density.

Human history is a journey on many dimensions – a journey of language, a journey of culture. To an energy nerd like me, however, it’s also a journey of power density. First we burned wood: Think of the amount of energy from burning a pound of wood as X. Then we burned coal – that’s about 1.8X. Then oil – 2.5X. Next, we split atoms: 2,000,000X – a huge advance!

Today’s clean energy technologies take us backward – not just pre-nuclear, but prehistoric. A typical coal plant produces around 100-200 watts per square meter of area, and a typical nuclear plant does about 400-500. But a typical utility-scale solar plant yields only about 10-20 watts per square meter – an order of magnitude worse.

As another example, while there’s plenty wrong with fossil-fired power plants, they have the virtue of being dispatchable – they possess a “volume knob” that lets us ramp their output up and down to match demand. In contrast, we only get solar and wind power when the sun’s shining and the wind’s blowing. We won’t replace coal with that.

As another example, while there’s plenty wrong with fossil-fired power plants, they have the virtue of being dispatchable – they possess a “volume knob” that lets us ramp their output up and down to match demand. In contrast, we only get solar and wind power when the sun’s shining and the wind’s blowing. We won’t replace coal with that.

A host of new, breakthrough energy technologies could outperform what we have today. They have been discovered, but not developed, and they’re ready to move from the lab into early-stage start-up companies. They span domains including energy storage, electrofuels, next-generation solar, thermoelectrics, advanced nuclear, and many more. These technologies are to the 21st century what photovoltaics were to the 20th.

So what’s holding them up?

. . . . .

We can answer that question by looking backward to see where past energy breakthroughs came from.

Let’s stick with power generation. When I look for the most recent example of a carbon-free power generation technology that reached mass adoption, I have to go all the way back to the 1950s. In 1951, scientists hooked a steam turbine up to a nuclear reactor and made emissions-free electricity (nuclear fission has its downsides, but “CO2 emissions” isn’t one of them). Three years later, researchers built the first practical solar cell (a photovoltaic with >1% conversion efficiency). Since then: nothing. How were these breakthroughs born?

We got nuclear fission from the Manhattan Project, a wartime effort sparked by fear of Nazi hegemony that cost $26 billion in today’s dollars. Nothing like it exists today.

We got nuclear fission from the Manhattan Project, a wartime effort sparked by fear of Nazi hegemony that cost $26 billion in today’s dollars. Nothing like it exists today.

Solar power came from Bell Labs, a massive corporate R&D operation lavishly funded with monopoly profits. We don’t have those any more.

“But Matthew,” you interject, “that’s not how we fund innovation in the 21st century. Today breakthrough technologies get productized by start-up companies, which are primarily funded by venture capital. We should look to start-ups – not government labs or corporations – for the next energy breakthrough.”

Rarely, venture capitalists make early-stage investments in energy game-changers – which historically need more than a decade to develop and even longer to scale up. But for the most part, that time frame is too long, the amount of capital required is too great, and the risks are too high. Venture investors need to show a return within 10 years, so they stick with what works, namely faster-developing businesses with lower capital requirements – think Instagram, bought for $1 billion at three years old with just 14 employees! When VCs do hard tech, it’s mostly in industries like pharmaceuticals that have much higher profit margins (and attendant valuations) than in energy.

Venture investors are smart. They know that there are fortunes to be made from transformative energy technologies, because the markets are huge. They’d be happy to back a truly breakthrough energy tech company – but only after its earliest stages, once a substantial amount of risk has been retired and the time-to-exit fits in a 10-year box.

This puts VCs in a race to be second. When no one is willing to go first, breakthrough companies don’t get launched.

PRIME’s mission is to go first.

. . . . .

PRIME is the brainchild of Sarah Kearney. Sarah ran the Chesonis Family Foundation, which between 2007 and 2010 disbursed $10 million in grants for energy-related science and engineering research at universities, primarily MIT. In parallel, she assisted the foundation’s benefactor with investments in clean energy start-ups. In the process she saw how the most game-changing ideas were paradoxically the least likely to be financed by traditional VC.

I met Sarah in 2010 when I was making venture investments in energy at Venrock. I roamed the halls of elite universities, getting to know the most enterprising professors and grad students whom I might earn the right to fund. At many of MIT’s best labs, I heard the same thing: A mysterious woman had shown up months before me and made a grant. I figured I should get to know her.

Over a period of years, Sarah and I traded notes on energy investing and the problem of early-stage funding. In January 2013 – after spending two years and an MIT master’s thesis on the topic – she sat across a table from me and outlined a solution:

- Family foundations command lots of capital – $600 billion in 2011, of which $47 billion went out in grants.

- Only 0.1% of this money went to energy innovation – despite the fact that many foundations believe in the power of technology to transform energy.

- Foundations aren’t absent due to lack of interest, but because of two barriers. First, they have no way to distinguish the truly promising candidates. Second, if they want to do anything creative, the transaction costs are high.

- A new intermediary could smash these barriers. On one hand, it could do the hard work of selecting and diligencing candidate companies, which requires deep domain knowledge. On the other, it could bring legal and accounting resources to bear that could reduce transaction costs.

- If done right, this intermediary wouldn’t simply channel grants. It would enable philanthropic organizations to use a more advanced set of tools that let them earn a return on their concessionary dollars in the event of a breakout success – yielding more money to be given away in the future. These tools include program-related investments (PRIs) and recoverable grants. (Hence PRIME: Program-Related Investment Makers for Energy.)

I found Sarah’s ideas compelling and asked lots of questions about how the model would work in practice. We decided to team up to answer them. An intensive research process ensued over the next six months, involving about 150 interviews with donors, intermediaries, and generally smart people.

I found Sarah’s ideas compelling and asked lots of questions about how the model would work in practice. We decided to team up to answer them. An intensive research process ensued over the next six months, involving about 150 interviews with donors, intermediaries, and generally smart people.

While we found a very high level of interest in the philanthropic community, we encountered an equally high education hurdle. Energy tech was new to family foundations and so were tools like PRIs; combined, this meant that PRIME would have to prove out its thesis gradually, one transaction at a time.

As a result, PRIME set three goals:

- Raise sufficient operating capital to run a lean organization for two years. By mid-2014, eight visionary backers – six family foundations and two family offices – had stepped up to meet the target.

- Receive a 501c3 exemption determination from the IRS. This would make PRIME an official public charity with a mission to harness philanthropic capital for energy innovation. We got it in September 2014.

- Make a series of proof-of-concept investments to demonstrate the model (i.e. one-offs done with a “coalition of the willing” each time, not out of a committed fund). The first such investment was completed in May 2015.

. . . . .

The recipient of PRIME’s first investment is Quidnet Energy.

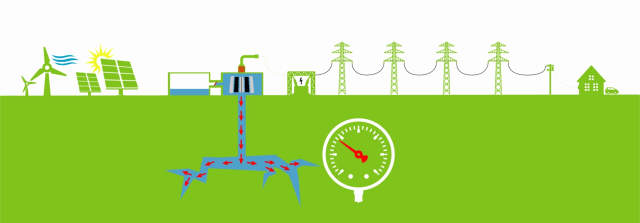

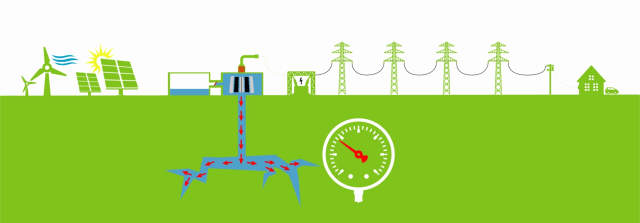

Quidnet tackles the problem of grid-scale energy storage – the mechanism needed to power the planet via renewables – with a radical new approach. It uses pressurized water as the storage medium within depleted oil and gas reservoirs. In the “charging” event, an electric pump pushes more water down, causing the reservoir to elastically deform – like a spring – and push back against the water. In the “discharging” event, a valve at the surface opens and the water rushes up to drive a pressure turbine, making electricity.

PRIME facilitated Quidnet’s seed investment, the initial injection of capital that brought it from concept to company. Four investors joined: the Sorenson Impact Foundation (which made a PRI), the Will and Jada Smith Foundation (which made a recoverable grant), and two angel investors (who issued straight convertible debt). The money is being used not to simulate how the technology would work in a computer model (that had already been done), but to test it for real at a carefully-selected site in central Texas.

Quidnet shows the hallmarks of a PRIME investment:

- A step change improvement. Most approaches to energy storage involve batteries. They are expensive. While these technologies can tap billion-dollar markets, they’re unlikely to reach the ultra-low-costs required to compete with fossil-fired generation. Quidnet can realistically achieve such low costs if the technology proves out.

- A compelling team. Quidnet’s founding team pairs a business leader – a seasoned energy tech entrepreneur with multiple companies under his belt – with a technical leader who has top-tier reservoir engineering experience.

- A high-risk experiment unsupported by conventional capital. The Quidnet seed round would not have happened but for philanthropic capital. When venture investors heard the pitch, their answer was “that sounds really promising and really risky – I’d like to learn more, but only after it works in the field.”

. . . . .

I co-founded PRIME and serve as chairman of its investment committee. (The other committee members will be announced this summer). We’re developing a comprehensive philanthropic investment process. It starts by screening the full universe of early-stage resource innovation projects (energy, agriculture, waste, water) for climate impact and for charitability, and then narrows them down based on attractiveness, misalignment with conventional venture capital, and potential impact at scale. An alpha version of this process led to the Quidnet investment, and the investment committee will go through a full-featured version of it this year.

I co-founded PRIME and serve as chairman of its investment committee. (The other committee members will be announced this summer). We’re developing a comprehensive philanthropic investment process. It starts by screening the full universe of early-stage resource innovation projects (energy, agriculture, waste, water) for climate impact and for charitability, and then narrows them down based on attractiveness, misalignment with conventional venture capital, and potential impact at scale. An alpha version of this process led to the Quidnet investment, and the investment committee will go through a full-featured version of it this year.

PRIME’s unveiling today is the result of two and a half years of work, and the intellectual and financial contributions of many smart, committed people. It’s our hope that there are many more investments to come – and that PRIME will help build long-term philanthropic capital into an established funding source for world-changing innovation.

On our second day we took a long hike up to Grinnell Glacier. You can see it from a distance in the right half of the pic below.

On our second day we took a long hike up to Grinnell Glacier. You can see it from a distance in the right half of the pic below. At the outset a ranger laid out the state of play: When Glacier National Park was established in 1910, there were 150 glaciers. Now there are 25. By 2030 there are expected to be zero. When we reached the end of the hike I continued another half-mile off-trail to the glacier’s edge.

At the outset a ranger laid out the state of play: When Glacier National Park was established in 1910, there were 150 glaciers. Now there are 25. By 2030 there are expected to be zero. When we reached the end of the hike I continued another half-mile off-trail to the glacier’s edge. This being 2015, what do we do? We take a glacier selfie…

This being 2015, what do we do? We take a glacier selfie… …before laying our hands on the ice.

…before laying our hands on the ice. As I walked back a disquieting thought came to mind. I’m 40 years old; my daughters are 11 and 13. Should I return with their children, there will be no more ice left to touch.

As I walked back a disquieting thought came to mind. I’m 40 years old; my daughters are 11 and 13. Should I return with their children, there will be no more ice left to touch.